The Magnuson Act

![]()

1875

The Page Act is signed into effect, banning specifically Chinese women from immigrating to the United States.

![]()

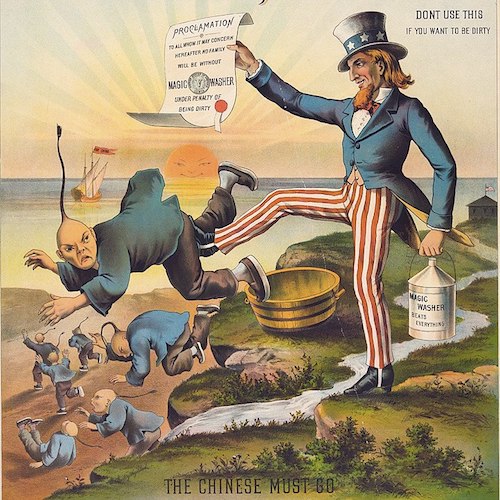

During the California Gold Rush (1848-1855), Chinese people begin to immigrate in higher numbers to the state of California. A large proportion of Chinese immigrants began building the infrastructure that was needed for the first transcontinental railroad.

After the Civil War subsided, the economy began to decline and many Americans blamed the Chinese for limited job availability. Anti-Chinese movements and animosity had started to take place, with some newspapers creating racist and vile anti-Chinese political cartoons.

Originally the Chinese Exclusion Act was supposed to be in effect for 10 years. It was then extended another ten years in 1892 by the Geary Act and finally made permanent in 1902. This meant that any Chinese person who was living in the United States that went outside of the country for any reason was required to fill out a form for re-entry.

![]()

1882

President Chester Arthur signs the Chinese Exclusion Act, becoming the first act to block a specific minority group from obtaining citizenship in the United States.

![]()

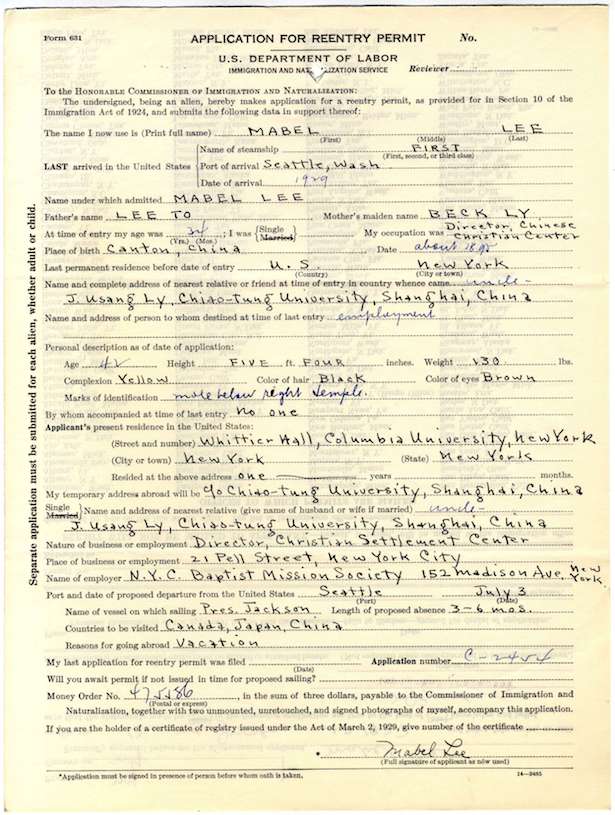

Dr. Mabel Ping-Hua Lee (1896-1966) won an academic scholarship that granted her a visa to the United States in 1905. She and her family moved to New York City’s Chinatown and settled while Mabel Lee attended Erasmus Hall Academy in Brooklyn. By the age of 16, Mabel Lee was an active member and well known in the New York suffragette movement. In 1912, she joined the parade that was organized by the New York suffragists where ten thousand people attended. Mabel Lee was on horseback and helped lead the parade from its starting point in Greenwich Village. In the same year, she began to study at Barnard College in New York City where Mabel joined the Chinese Students’ Association. In 1920, when the 19th amendment was passed, Mabel was not able to vote because of the Chinese Exclusion Act but this did not stop her and other Chinese suffragists from advocating for women’s rights, even if they did not benefit. In 1921, she graduated from Columbia University with a Ph.D. in economics. She became the first Chinese woman to do so. Later on, she would go on to found the Chinese Christian Center, which acted as a community center that offered English classes, a health clinic, and a kindergarten. Mabel Lee devoted her life to her community until she died in 1966. There is no known record if she was ever able to obtain U.S. citizenship or if she ever voted in an election.

Image courtesy of The New York Times, via National Parks Service

Lee's application for a permit to reenter the United States after completing missionary

work in China.

Lee's application for a permit to reenter the United States after completing missionary

work in China.

Image courtesy of the National Archives, via DocsTeach

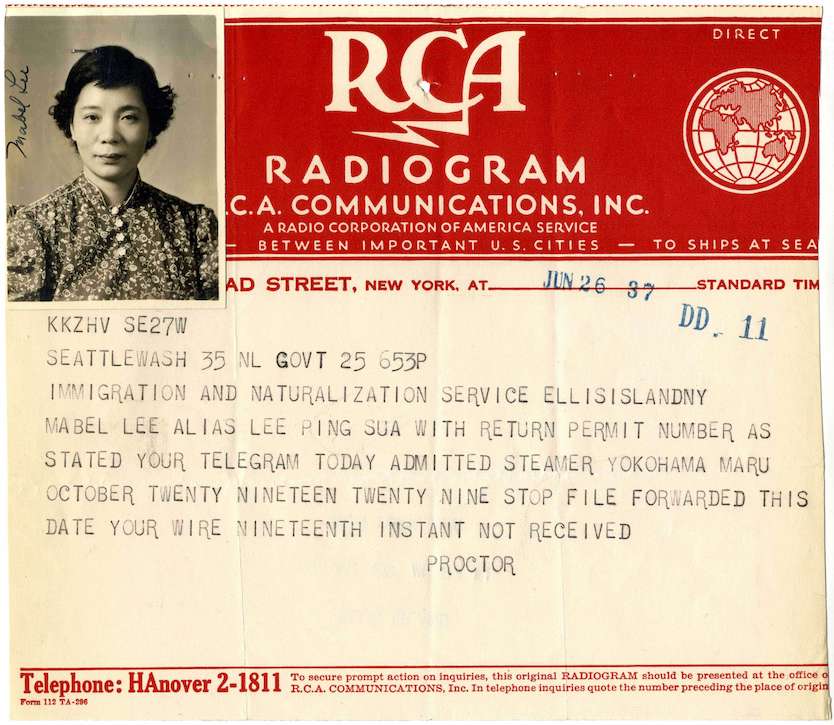

Radiotelegram confirming Lee's return permit.

Radiotelegram confirming Lee's return permit.

Image courtesy of the National Archives, via DocsTeach

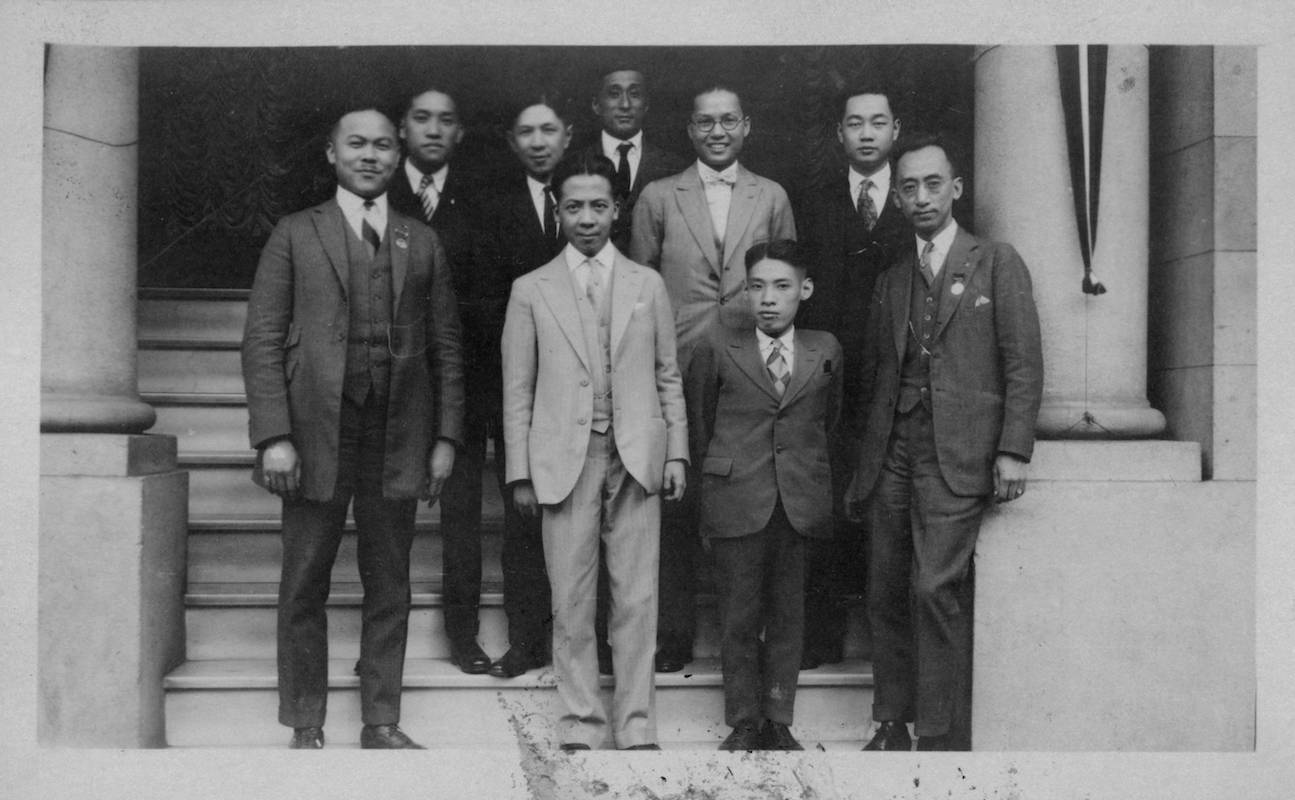

The Chinese American Citizens Alliance traveled to Washington D. C. to testify before the Committee on Immigration and Naturalization in the House of Representatives. Y. C. Hong is the second person from the right on the front row. Kenneth Y. Fung is the first person from the right on the second row. Henry Lowe is the first person from the left in the second row.

During World War II, China and the United States were allies, which led to the long-awaited repeal of the ban on Chinese immigration and naturalization. Chinese immigrants could apply for citizenship and could register to vote in their country.

Image courtesy of You Chung Hong Family Collection, Huntington Digital Library

![]()

1943

Chinese immigrants are given the right to citizenship and the right to vote by the Magnuson Act (Chinese Exclusion Repeal Act).

![]()

When making a contribution please be sure to select “library archives“ for your gift designation. We thank you so much for your support!