Civil Rights Era of 1950-1965

![]()

1865-1868

The 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the United States Constitution (dubbed the Reconstruction Amendments) are ratified.

![]()

The Amendments free all enslaved persons in the United States (13th), grant voting rights to all naturalized citizens (14th), and protect citizens’ voting rights regardless of “race, color, or previous condition of servitude” (15th). State governments continue to employ discriminatory screening practices like literacy tests and poll taxes to disenfranchise Black voters; this period is known as The Jim Crow Era.

1920 - Ocoee, Florida - On Nov. 1, 1920, Ku Klux Klan protesters march through Ocoee, Florida declaring that “not a single negro will be permitted to vote” in the labor settlement, which was almost 50% Black. On Nov. 2, Election Day, several Black community members attempt to exercise their legal right to participate in the Presidential election - all are turned away, either by threats of violence or “mysterious” issues with registration rosters. In response to his unlawful barring from the polls, Mose Norman attempts to secure legal backing from Judge Cheney in nearby Orlando, who advises Norman to collect the names of Ocoee’s Black residents that had been denied their constitutional right to vote in order to file a lawsuit against Orange County. In response to this legal affront, a white mob descends on the home of July Perry in an attempt to locate Norman. Perry, a Ocoee community leader and local deacon, is arrested and sent to the Orlando Jail. Once there, Perry is kidnapped from police custody by the white mob and lynched. Perry’s murder incites a race riot that results in the murders of as many as 60 Black Ocoee residents, the burning of Black-owned homes and businesses assessed at over $4.2 million, and the forced removal of Ocoee’s ~500 remaining Black residents. For 18 years following the Ocoee massacre, not a single Black vote is cast in Orange County.

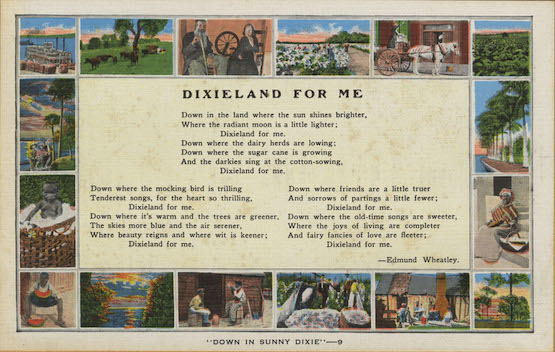

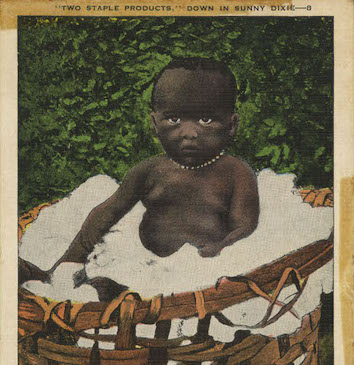

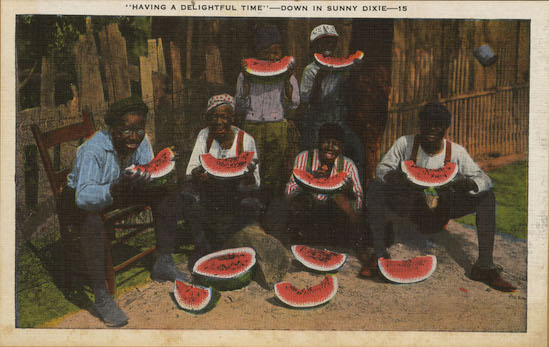

Racist imagery was used as a way to reinforce hatred and bigotry towards newly-freed Black Americans in the Jim Crow Era. Similar to political cartoons, racist postcards were a way to mass-produce and proliferate racial stereotypes. This widespread campaign of hatred garnered public support for the continued legal suppression of Black people’s rights into the 20th century.

Viewer Advisory: The postcards below portray harmful and extremely racist imagery/language. The Bradshaw Library Archives does not support these views; their presence here is to provide necessary context on the social climate of Southern states in the Jim Crow Era.

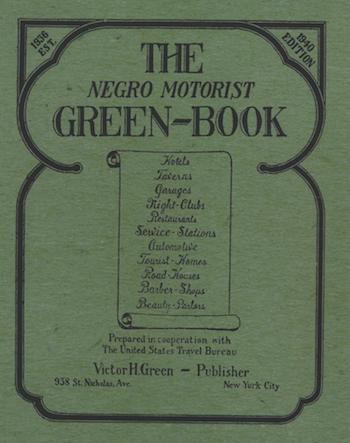

1936 - New York City - The first edition of The Negro Motorist Green Book is published by former postal employee and travel writer Victor H. Green. Black Americans' safety, particularly in Southern states, was not guaranteed in the Jim Crow Era. Despite a growing population of affluent, educated Black Americans, very few businesses adapted to cater to this growing customer base; in fact, certain Southern states enacted "sundown laws," all-white communities which prevented the presence of Black people through violence, discrimination, and Jim Crow-era legal discrepancies.

“The Negro Motorist Green Book, first published in 1936, was a product of the rising African-American middle class having the finances and vehicles for travel but facing a world where social and legal restrictions barred them from many accommodations. At the time, there were thousands of “sundown towns,” towns where African-Americans were legally barred from spending the night there at all. The book provided a guide to hotels and restaurants that would accept their business, and often promoted businesses established specifically for the black customer.” - From “History,” Green Book. Image: Green Book from Florida Gulf Coast University Bradshaw Library's Archives and Special Collections Permanent Collection.

![]()

1954

Brown v. Board of Education unfolds. Black students gain the legal right to study alongside their white peers.

![]()

"The decision fuels an intransigent, violent resistance during which Southern states use a variety of tactics to evade the law.”

- from A Long Struggle For Freedom, Library of Congress.

![]()

1955

Nationwide protests erupt after the murder of 14-year old Emmett Till. Till was brutally lynched and disposed of in a river after allegedly harrassing a white female clerk at a grocery store.

![]()

Till’s mother insists on an open-casket ceremony in order to expose the world to the savagery of racial discrimination in the South. The murder of Emmett Till fuels protests across the nation.

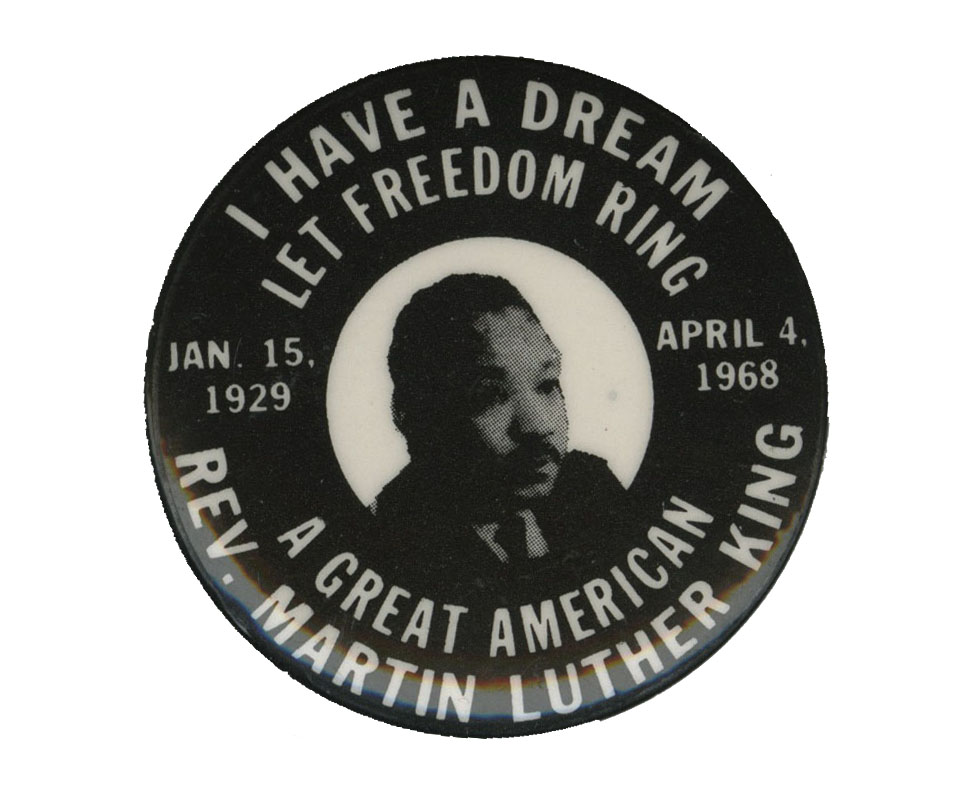

1955 - Montgomery, AL - “Bus boycott led by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., begins a campaign of nonviolent civil disobedience to protest segregation and attracts national and international attention.” - From A Long Struggle For Freedom, Library of Congress. Image: Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial pin from Florida Gulf Coast University Bradshaw Library's Archives and Special Collections Permanent Collection.

1956 - Little Rock, AK - A group of Southern lawmakers sign the “Southern Manifesto,” which pledges resistance to racial integration by all “lawful means.” Public and legislative resistance flares during the crisis over integration at Little Rock, Arkansas’ Central High School. Elizabeth Eckford is part of a group of recruited students who integrate the high school after the NAACP registers them without the consent of local lawmakers. A large, aggressive group of white protesters gathers in front of the school to meet the students on their first day. Pictured is Elizabeth Eckford, 15, wearing sunglasses while being jeered at by Hazel Bryan, also 15. Image courtesy of US Embassy: The Hague via Flickr.

![]()

1960

NAACP Youth Council chapters stage sit-ins at whites-only lunch counters, sparking a movement against segregation in public accommodations throughout the South.

![]()

"Nonviolent direct action increases during the presidency of John F. Kennedy, beginning with the 1961 Freedom Rides.”

- from A Long Struggle For Freedom, Library of Congress.

![]()

1961-63

Hundreds of demonstrations erupt in cities and towns across the nation. National and international media coverage of the use of fire hoses and attack dogs against protestors cause a crisis in the Kennedy administration.

![]()

"The bombings and riots in Birmingham, Alabama, on May 11, 1963, compel President John F. Kennedy to call in federal troops.”

- from A Long Struggle For Freedom, Library of Congress.

1963 - Jackson, MS – Medgar Evers, World War II veteran and prominent social justice leader in the South, is assassinated in his home. His murder came after months of harassment and death threats. Evers’ killer, Byron De La Beckwith, is tried and not initially convicted of the fatal shooting. Public figures, including then-governor Ross Barnett, express their support for De La Beckwith. Two all-white juries reach a deadlock, and De La Beckwith is acquitted. 31 years later, De La Beckwith is retried and sentenced to life in prison.

In August, two months after Evers’ assassination, the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom takes place in the nation’s capital. The march rouses public support for President John F. Kennedy’s comprehensive civil rights bill, then-pending in Congress. Kennedy’s assassination on November 22 leaves the fate of the bill in the hands of his vice president and successor, Lyndon B. Johnson.

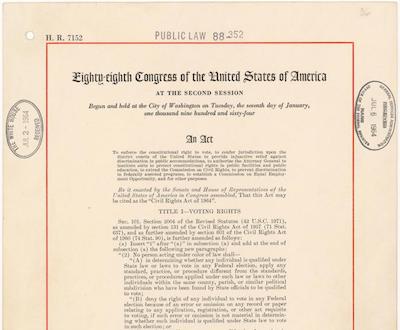

1964 - Washington, D.C - After continued protests and the public support of President Lyndon B. Johnson, the House of Representatives and The United States Senate pass The Civil Rights Act of 1964 in February and June, respectively. President Johnson signs the bill into law on July 2. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlaws discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin; it also prohibits biased voter registration requirements and racial segregation in schools, employment opportunities, and public accommodations (buses, water fountains, restaurants, etc.). Image courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.

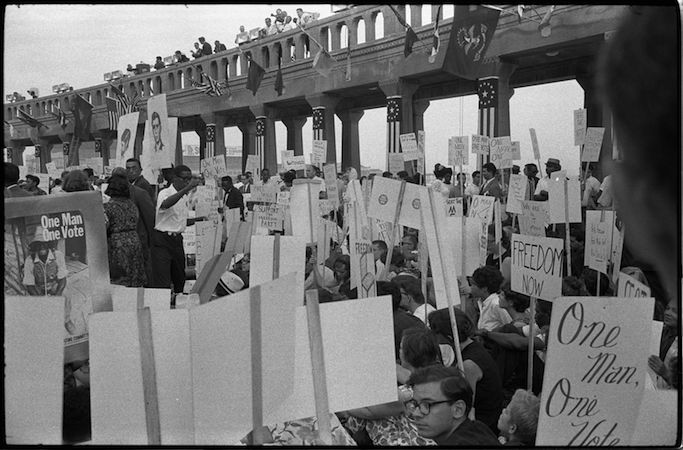

1965 – Selma, AL – A peaceful civil rights march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge led by John Lewis and Reverend Hosea Williams is met with police resistance and brutality. Sheriff Jim Clark orders all white males in Dallas County to report to the courthouse to be deputized, and demonstrators are told to disband and return to their homes. Reverend Williams attempts to speak to the officer in charge and is rebuffed. The troopers attack the demonstrators shortly after, launching tear gas and charging the crowd on horseback. Televised images of the violence spread across the globe and help rouse support for the Selma Voting Rights Campaign. John Lewis, who would go on to become a U.S. Congressman and civil rights icon, is left with a skull fracture and scars on his head. In all, 17 marchers are hospitalized and 50 treated for lesser injuries in what would become known to history as “Bloody Sunday.”

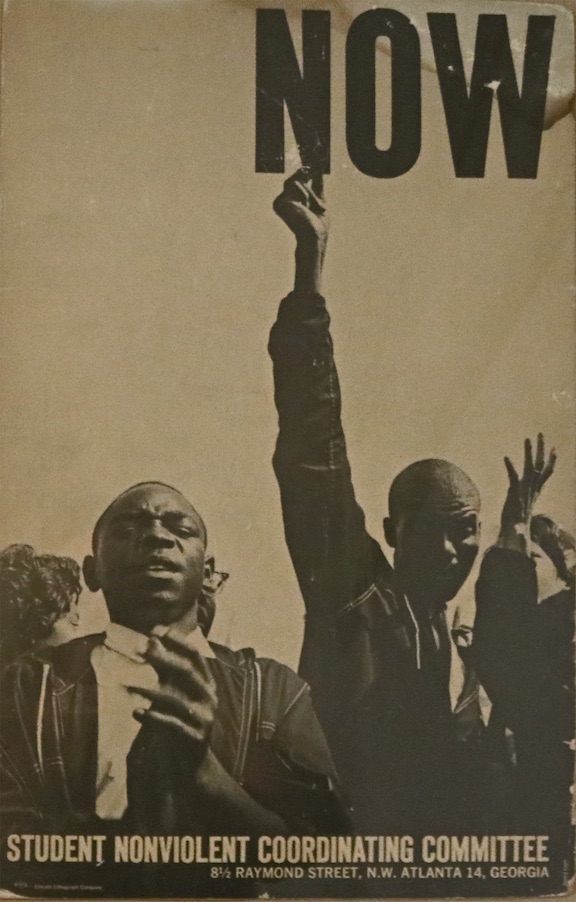

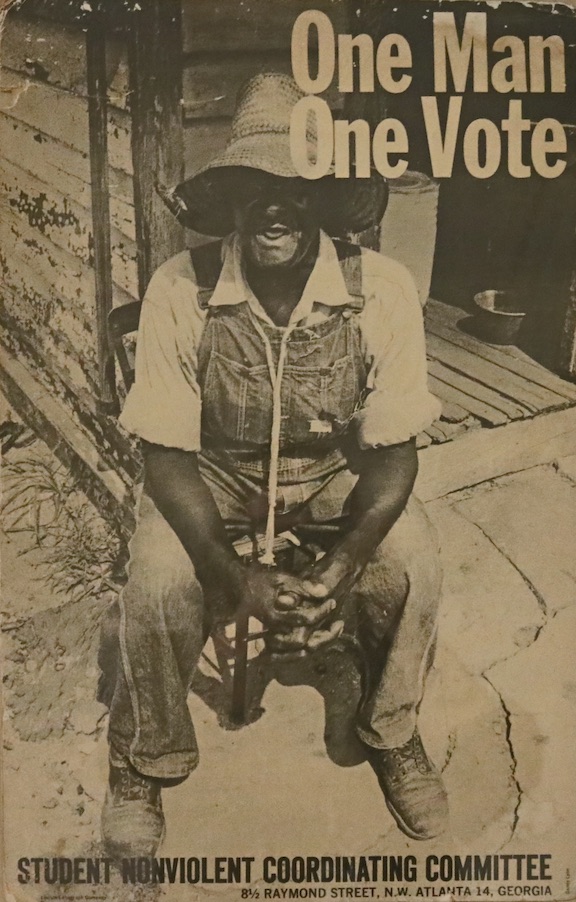

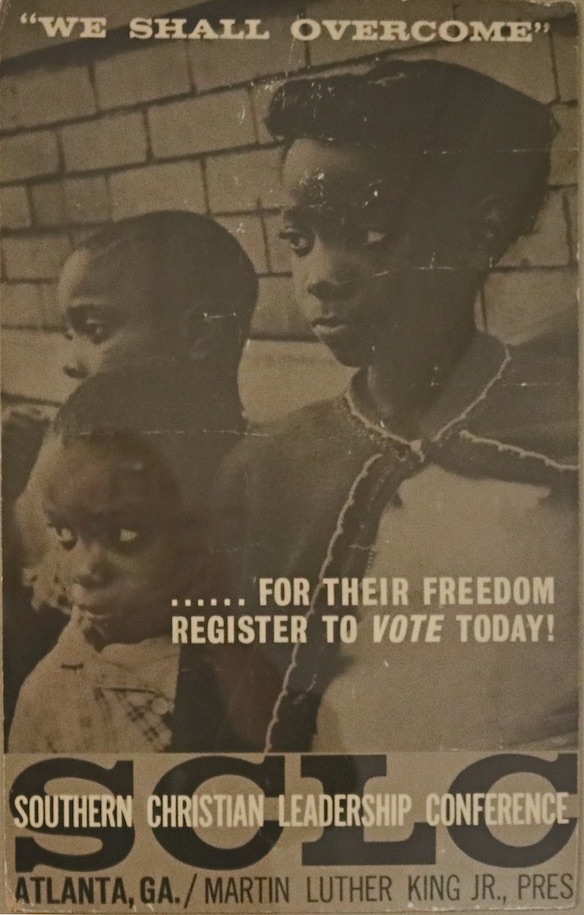

Civil Rights-Era Posters

These posters were graciously loaned by Howard Simon.

All three of these posters were produced by the Lincoln Lithograph Company and issued by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). The SNCC was formed in April 1960 by a group of students, led by Ella Baker, from Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina. The group supported numerous civil rights events such as lunch counter sit-ins, freedom rides, and numerous marches. Danny Lyon was the official photographer for the SNCC and participated in almost every major Civil Rights Movement event. All of the images seen here were taken by Danny Lyon.

![]()

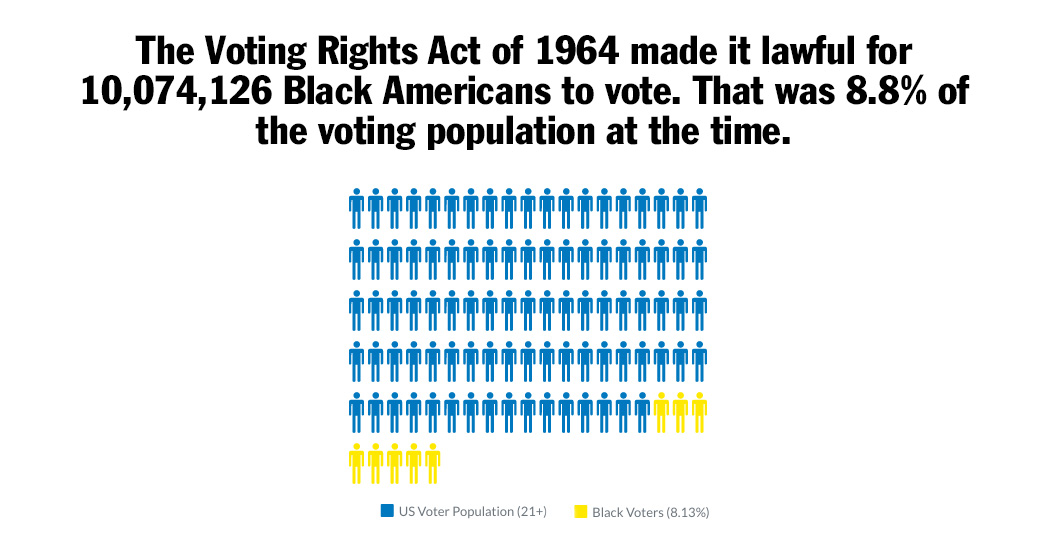

1965

President Lyndon B. Johnson signs and enacts the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The act protects voter registration and voting for racial minorities.

![]()

The act is put in place to correct discriminatory election systems and district boundary issues that largely targeted Black voters.

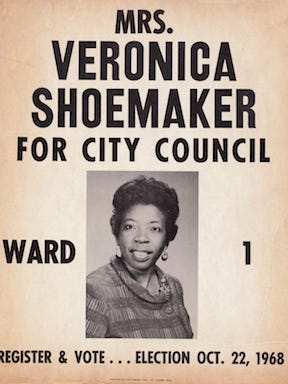

1968 - Fort Myers, FL - Veronica Shoemaker begins her campaign to sit on the City Council of Fort Myers. After 17 runs for office, she is elected in 1982 and becomes the first Black person to hold a local City Council seat. Veronica Shoemaker was born in 1928 and lived on a dirt road in Dunbar. As a child, Shoemaker worked for a gladiolas farmer and held a part-time position in a flower shop, where she resolved to one day own her own business. In addition to her work as a prominent florist, Shoemaker was a active leader in the Fort Myers community, and was determined to become a part of the City Council in order to advocate for the equality of Fort Myers’ Black citizens. During her time on the city council from 1982-2007, Shoemaker helped desegregate Lee County schools, advocated for the enactment of a ward system to increase Black representation in local governments, and enriched the community through the creation of the Harborside Event Center, the IMAG History & Science Center (formerly the Imaginarium), and the City of Palms Spring Training Center for the Boston Red Sox. Shoemaker was also the President of the local chapter of the NAACP, and was the first recipient of Hodges University’s Luminary Award. Shoemaker died in 2014 at the age of 86, leaving behind a legacy of social justice, community enrichment, and a successful flower shop on Martin Luther King Jr. Blvd in Fort Myers.

Image courtesy of the Lee County Black History Society. If you would like to learn more about Veronica Shoemaker, please visit the Lee County Black History Society.

“It was nearly impossible for a black person to win office,” said former Fort Myers Mayor Wilbur Smith, who served on the council with Shoemaker for 14 years. “But Veronica Shoemaker never gave up on anything or anyone.”

- from "Veronica Shoemaker" by Cody Dulaney, News Press, Jan 21, 2016

Next: Explore Voting and the Military

When making a contribution please be sure to select “library archives“ for your gift designation. We thank you so much for your support!