Yesterday, It Was Sunny: Solo Exhibition of work by T.L. Solien

T.L. Solien is known for his personal, surrealist paintings combining everyday objects in haunting landscapes and interiors. For this exhibition the technique of collage features prominently in the development of his works. Solien’s freeform collages will be on display alongside his paintings and drawings, offering a unique glimpse into his narratives and working process.

Wasmer Gallery - Curated by John Loscuito - Sponsored by Gene and Lee Seidler and WGCU Public Media

Born in 1949 in Fargo, N.D., and currently professor of art at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Solien earned a B.A. at Minnesota State University Moorhead (1973) and a M.F.A. from University of Nebraska-Lincoln (1977). Solien has taught studio courses at The Ohio State University, The University of Iowa, and Montana State University. He has been a faculty member of the University of Wisconsin since 1997.

He gained attention for painting, sculpture, and works on paper that combine cartoon-like and surreal imagery with references to art and cultural history, while also exploring his life, mind, and emotional states as a man, artist, husband, and father. Solien has appeared in numerous national group and solo exhibitions at venues that include the Whitney Museum of American Art, Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Walker Art Center, Des Moines Art Center, Madison Contemporary Art Museum, and the American Center in Paris. His work is held in the collections of the Tate Modern, Whitney Museum, Walker Art Center, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Art Institute of Chicago, National Museum of American Art, the High Museum, Rhode Island School of Design, The Sheldon Museum, The Plains Art Museum, and other public collections. He lives in Madison, Wisconsin with his wife, Deborah.

T.L. Solien, Small Room, 2004, Oil on canvas,

60 x 72 in. Courtesy of the artist

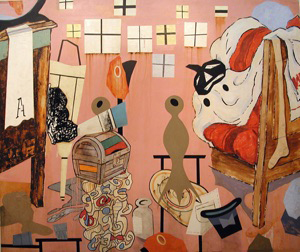

T.L. Solien, Seam, 2014, Acrylic and enamel on canvas,

60 x 72 in. Courtesy of the artist

T.L. Solien, Piker Jersey, 2012, Mixed media and collage on paper,

30 x 36 in. Courtesy of the artist

The following are excerpts from an interview between T.L. Solien and John Loscuito, FGCU Art Galleries Director, conducted August, 2015.

John Loscuito - In the FGCU Art Galleries exhibition it is evident that collage uniquely informs your painting style. Could you explain the role collage plays in creating your characters and compositions?

T.L. Solien - I’m going to start by talking about how I started working with the collage process. I was working on this long-term project that involved a response to Moby Dick, as it is attached to the greater 19th century American history. When I started working on this Moby Dick series, I realized that what I needed to do was use materials that came from a broader, popular cultural source; like xerox, posters, or fragments of illustrations. I wanted to juxtapose those things and try to construct an image fabric that was unlike anything that I had used or developed in the past. Eventually this included having to make very small, tightly edged linear elements, and I discovered that I just couldn’t do that using conventional drawing and painting materials. So, I started to cut paper to solve that problem.

John Loscuito - Are your narratives specifically linked to the novels Moby Dick and Ahab’s Wife? Is it critical for the viewer to make those connections?

T.L. Solien - I think there are lots of entry points for this work. Generally speaking, all the work is autobiographical. I just find avenues through popular culture, literature, and film and other material cultural veins in order to inject my own attempts to understand my own life experiences.

John Loscuito - When you say they are autobiographical, do you see yourself in certain objects or landscapes?

T.L. Solien - What I am talking about has more to do with the way that I respond to the narrative that I choose to use as a grounding mechanism. For instance, with Ahab and Ahab’s widow, Ahab was extraordinarily compulsive, mortally compulsive. He was also utterly dedicated to his fixation - killing the white whale. His relationship with his family obviously suffers because of that fixation in as much as it kills him; but it also meant that as a whale ship captain out at sea, killing whales for four or five years at a time without coming back to port, that he’s obviously distancing himself from his family in some way that, I would imagine, has a profound effect on his relationship with his family.

When I was reading Moby Dick and coming to these realizations as to how to read the characters I began to see that the relationship Ahab had with his wife was very much like the relationship that I have with my wife and family because I’m an artist. I’m compulsively working in the studio as much as I can. I saw my own personality within Ahab’s personality. I saw my wife’s personality within Ahab’s wife’s personality. I imagined how my wife might live out her life after my possible death and I tried to inject that same spirit of adventure and accomplishment and independence into the character of Ahab’s widow as it is experienced through the tableaus that I created in support of that body of work.

John Loscuito - In some of the paintings, especially in some of the more recent ones, the policeman starts appearing. He’s a dark and ominous figure. I’m wondering what drove that figure to appear?

T.L. Solien - The first time I used one was in response to the killing of a musician by a cop. The musician was walking home drunk after playing a gig and he was so drunk that he attempted to enter the front door of the house next to the house where he lived. The people that lived in that house thought he was a burglar and they called the police. So, this cop shows up and confronts the drunk guy who is weaving around and, according to the policeman, being very threatening. The guy was 5’6” and 125 pounds and the cop shot him and killed him on the sidewalk in front of the house. That incident started this use of the policeman figure for me. That’s what spawned it. Subsequently, there have been other rationales, other conceptual rationales, for using it and this is where it starts to get into very complicated explanations.

John Loscuito - That’s an interesting function of art. Works that are more open to interpretation allow for new points of relevance depending on what our history reveals to us as we live it, as we make it.

T.L. Solien - Yeah, well, if you notice the cops in the two works that you are borrowing, I’ve tried to make them dysfunctional. In the drawing, Cop with Potato, I’ve tried to take away the threat. I’ve tried to recognize the threat in the facial description of the cop. The cops are sort of skeletal and monstrous; like nightmare cops or clown cops. I’ve given them no weapons. The cop has a potato, so his power is a potato. If cops didn’t have guns in America, I don’t think they would be very dangerous. So you take away the gun and you replace it with a potato and you’ve basically disarmed the cop.

In the painting called Seam, the cop has extraordinarily large hands and fingers. He couldn’t possibly pull a trigger. The title of the painting refers to the black line that goes between the cop figure and a suicidal woman on the rooftop. There might be an inclination for the cop to assist in the saving of this woman from jumping, but because his hands are so big and he can’t fight through the membrane of the black line that exists between the space that he’s in and the space that she’s in, he becomes completely dysfunctional in that way as well.

John Loscuito - There are a couple of other paintings that I’m curious about, Piker Jersey and Eberman’s Jersey. I haven’t quite figured out the reference. Do you mind sharing that information?

T.L. Solien - The Fireman series comes into play in terms of Ahab’s widow seeking romantic relationships. In the larger body of work that I made dealing with that, there are instances where it seems as though Ahab’s widow is involved with another woman, involved with fur trappers, involved marrying a Native American man. All are trying to allude to, without putting one figure next to another figure, her relationship with a volunteer fireman in a fictional Plains States town.

Male figures come into that body of work sometimes just as articles of clothing. I had visited this fantastic museum in Kearney, Nebraska that is a pioneer museum, and one of the rooms they had in that museum was dedicated to early fire departments. Circling the walls, they had vestiges of fireman’s uniforms and some of them were partially burned, some were moth eaten, the red dye had been bleached out or some of them irregularly colored and they were just hanging on hangers, hanging on the wall. They were so powerful, they just blew me away because everything was there in that object. The residue of the human beings who wore them; the historical experience; the work of being a fireman itself; heroism, perhaps.