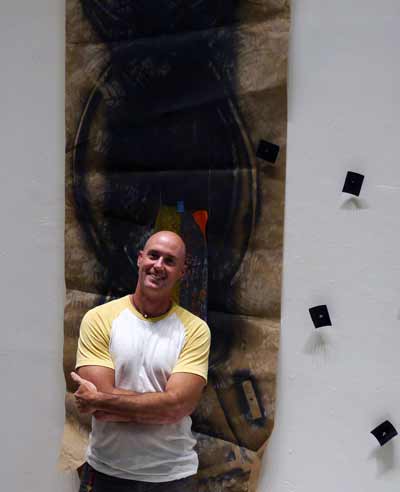

Michael Massaro, The Vanishing, 2016, Mixed media installation, Dimensions variable. Photograph by Anica Sturdivant

The Vanishing

Michael Massaro

ArtLab Gallery

February 11 - March 17, 2016

As part of the Crossroads of Art and Science Residency, each year an artist is invited to spend time working and thinking alongside the science faculty at FGCU’s Vester Marine and Environmental Science Research Station. While in residence Michael Massaro will be creating new art work, engaging with students and installing an exhibition in the ArtLab Gallery. Artists chosen for this residency work to illuminate the relationship between art and science.

Sponsored in part by Alice and Dean Fjelstul, The State of Florida, Department of State, Division of Cultural Affairs and The Florida Council on Arts and Culture, WGCU Public Media, and The Beaches of Fort Myers and Sanibel.

The following interview was conducted by Gallery Director, John Loscuito with Resident

Artist, Michael Massaro

JL: What piqued your interest about the Crossroads of Arts and Sciences at FGCU and

also the marine science research of Dr. James Douglass?

MM: When you drive into FGCU, you realize it is very different from the roads leading

up to it. When you get to the campus, you see the natural non-invasive species. The

fact that the flat wood pine forest is left alone to do what it does tells you it

and its ecological function is important to the university. When I read about the

work that James Douglass is doing, it seemed so ambiguous to me. As an artist, I want

to go where I haven’t been before with a level of experimentation. When we met, James

and I hit it off on a personal level and that was important. When you are going to

collaborate and are dealing with their research, the scientist has to have a certain

amount of trust that I will handle the topic correctly.

JL: James Douglass is exploring the beneficial effects of seagrasses in Southwest

Florida and you began doing your own research as well. What was that process?

MM: Immediately after we agreed to work together I began to do my own research. I

knew this would be necessary because of my lack of real knowledge about seagrasses.

Even though I grew up near the ocean, I never explored it on this deeper level. I

found out what I didn’t know first, which is usually this case, beforehand. The meeting

with James gave me a point from which to start. I struggled with what to do with seagrass;

it’s a difficult material to work with unless you are going to draw on it or paint

on it. I’m a very process oriented person and it wasn’t until I decided to make paper

that I thought I had a direction. Then everything took off.

JL: The seagrasses inspired a couple pieces on campus. One is a collaborative piece

with Patricia Fay’s ceramics students (installed in the courtyard of the Arts Complex)

and others are pieces you are producing for the ArtLab Gallery. How did you approach

these differently?

MM: I treated both as different projects knowing that one was outside and had to be

made of something that is going to stand up, not only to weather and time, but also

to the collaboration. Anything that is in the gallery is just from my mind and my

creation and has to stand up to me. I knew that the materials would be more limited

outside. For one thing, it had to be transported and broken down. I also had to leave

room for the class to be able to enter the collaboration. If I made a form that was

closed off and limiting to them, my ego would be the only thing that shows up and

that was not my intention. I really streamlined the structure so it would be clean

and dynamic so they could respond to it, but it also challenged them creatively.

JL: These two approaches show your range in use of materials and how an artist can

interpret subject matter in vastly different ways. How does this relate to some of

your past exploration of materials?

I am process orientated and material oriented. With any of my sculptures, I think

about the material first. Why am I using one material when I could be using another?

The outside sculpture had certain criteria and for the sculptures in the gallery I

chose bamboo because it is a type of grass and has a lot of strength. I played with

other materials as well, but they did not work in my tests. I also liked that it

is an organic material. Materials are paramount to me and when I think about my subject

matter I think about the material.

JL: Is there a theme you are investigating that explores ideas about natural and manufactured

structures; discussing how we are inspired and learn from our environment?

MM: Yes, even before this I was looking for a balance between natural materials and

manufactured materials. The bamboo sculpture I made also combines metal in the structure.

I wanted to create it the same way that someone creating a fish trap would make it,

so the process of building the structure was more important than the aesthetics. I

try to get into that mode so I’m not just making an object, I find that it helps my

process. I see that everything is connected and as I am building, I am absolutely

thinking about the way different things connect, how the ideas connect and how materials

are typically used. I am also discovering things about bamboo that I didn’t know because

I had never worked with it on a scale that is twenty to thirty feet long.

JL: Scale is something I was also going to ask you about because all the pieces transform

things that are relatively small or even microscopic into pieces that are larger than

life. Was this massive change of scale something you intended to do as you were developing

the work?

MM: Scale was one of the first things I thought about when I saw the gallery. The

space is unconventional being as tall as it is and with two concave bay windows. It

feels like an aquarium, as if you were to go to an aquarium with different floors.

The echo in the room makes it feel vast. As I work, people come by and look in and

I feel like a fish in a tank, like they are stopping by to see what is swimming around.

I have encouraged them to come in and I keep the doors open. I am trying to use the

height of the room as much as possible, that is one reason for the scale. I want people

to have to look up instead of what is normal, looking down from a dominant perspective.

I want that sense of “I’m not in control of this and it’s bigger than me,” and that

is based on the subject matter coming from my research.

JL: In your sculptures you have set up a relationship between an oversize fish trap

installed across from a large sheet of paper made of seagrass. I can’t help but wonder

about that meaning.

MM: It goes back to the process. I don’t feel the viewer has to make those connections.

With the nature of the project I feel that I should be getting people interested in

James’ work. If I do that in any shape or form, then job well done. They don’t have

to understand everything but in the process I was thinking about how you would use

a fish trap in the seagrass, the seagrass is where the fish will be and without the

seagrass there isn’t anything to catch. The answer changes as I continue to work with

the forms. I had preconceived notions about the fish trap sculpture before I built

it and as I got into it my feeling about it changed very quickly. Unlike other exhibitions,

this is a residency and I am building the work here without knowing how it is going

to work. I wanted to treat it differently and I think that this, along with having

the interaction with the students, has changed my process.